The RL Community Hub will be launching on September 15th to provide TA leaders access to big industry discussions, resources, events, and more.

Facilitating neuro-inclusivity for the neuro-diverse

It’s unclear to the casual observer what else Theo Smith and Dominic Cummings might have in common, but a firm and passionate belief in neurodiversity ties them closely together.

In an announcement perhaps lacking absolute best resourcing practice, government advisor, Cummings initiated earlier this month a major civil service recruitment drive, seeking to broaden the Whitehall gene pool. Instead of Oxbridge types, Cummings wants to attract ‘untapped bright minds’, ‘wild cards, people who never went to university’, ‘who fought themselves out of a hell hole’. What Cummings is clear about is the recruitment of those with ‘genuine cognitive diversity’.

Music to the ears of RL100’s Theo Smith. Theo tells his own deeply personal story. A story of not fitting in, nor wanting to fit in, at school. Of being more comfortable on the outside. A story of self-diagnosing not only dyslexia but also ADHD.

But that’s not to suggest for a moment that Theo’s story wasn’t hugely uplifting. That his own experiences as both an individual and a father haven’t opened his eyes as to what might be achieved for the neuro-diverse in the workplace – over and above the progress currently being made.

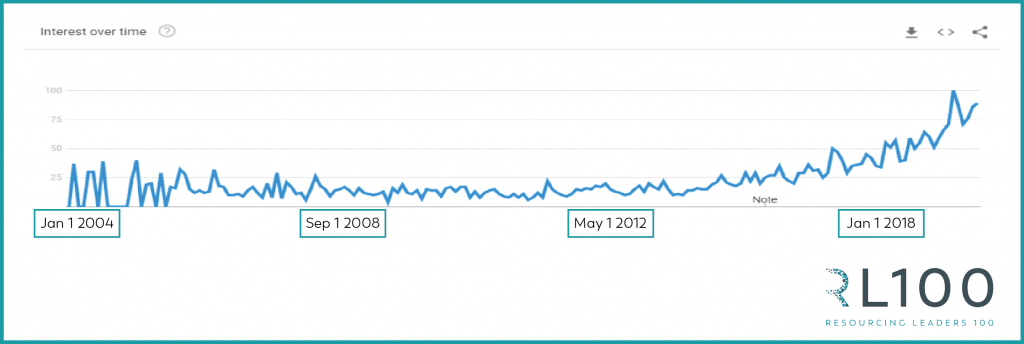

In the midst of his talk, Theo displayed a graph which illustrated the increase of neuro diversity-related web searches since the RL100’s first set of content on neurodiversity dropped in 2018.

50% of working-class men with dyslexia end up in prison at some point in their lives, whilst around two thirds of self-made millionaires share this neurodiversity, suggests both the predicament and the potential of such conditions.

And whilst the successes of dyslexics such as Sir Richard Branson, Charles Schwab, Lord Alan Sugar, Jamie Oliver and IKEA’s Ingvar Kamprad are hugely impressive, pointing to what neuro divergents can achieve, these are achievements they had largely to create themselves, not from within an established corporate environment.

Here, then, is the essence of the challenge for those candidates with dyslexia, dyspraxia, ADHD, autism or dyscalculia (or indeed a combination thereof).

Employers are increasingly interested in such individuals. There are a growing number of hugely successful case studies from the likes of IBM, SAP, RentalCars, Microsoft, the BBC and LinkedIn. Little wonder given both the hugely competitive labour market – the most recent KPMG/REC survey from earlier this month pointed to sharp increases in starting salaries and temp wages and there remain more than 800,000 open vacancies across the UK economy – and the perception that such neuro-divergent talent will look at problems and solutions differently. They zig when the neuro normal will zag. If we talk increasingly about the challenges of a VUCA world, then the neuro-diverse have spent their lives in such an environment.

For GCHQ, an organisation that has been proactively recruiting the neuro-divergent for more than 20 years, they are proud that their workforce represents ‘a mix of minds’.

With business and organisational change nearly a constant, such people will be more comfortable with risk, with the apparently illogical or seemingly unpolitical.

Despite the overwhelming argument as to why organisations should reach out more enthusiastically to people with such characteristics, metrics suggest this has yet to genuinely take off.

80% of people on the autism spectrum are unemployed. A survey from the CIPD suggested that 72% of UK employers ignored neurodiversity in their policies. And according to the National Autistic Society, 60% of UK employers admit to not knowing where to go for support and advice about employing an autistic individual.

So, two questions to our community and our industry. What sort of candidate experience might a neuro-diverse individual encounter when applying to your organisation?

And, once an employee, how welcoming is your workplace to such people?

Let’s examine the first point. Organisations are seeking to make their candidate journeys consistent and cohesive. This makes abundant sense in terms of fairness but does not always play to the strengths of the neuro-diverse. Those organisations that have demonstrated real success in such initiatives have adopted a greater deal of flexibility – ‘SAP focuses on scalable HR processes, but if we were to use the same processes for everyone, we would miss people with autism’, suggests Anka Wittenberg from the German software giant.

When was the last time your organisation audited its recruitment process to ensure that the neuro-diverse were not being excluded?

Once people from such backgrounds land in the workplace, they can be faced with two challenges – one cultural, one physical.

The neuro-divergent tend to flourish with natural lighting, rather than harsh overhead lights, according to Nancy Doyle from Genius Within. Similarly, they can be distracted by background noise and open plan environments to a much greater extent than the neuro normal – consider noise-cancelling headphones. The use of mind mapping software also makes their employee experience more rewarding.

Again, it would be fascinating to understand the extent to which RL100 employers have gauged the employment experience of their neuro-divergent people.

As Sean Gilroy from the BBC suggests, ‘Organisations are good at physical accessibility but considering cognitive accessibility isn’t really well appreciated’.

From a cultural perspective, important workforce traits such as effective team working and emotional intelligence are quite rightly lauded. However, they do not necessarily play to the strengths of autistic employees.

Perhaps even more fundamental – and something Theo also touches on – are the people management skills of those that the neurodiverse report to. How used to managing such individuals are they? How empathetic are they? As Theo suggests, organisations can often see the neuro-divergent as possessing super powers. They increasingly see their abilities not as a disadvantage, but as a real organisational differentiator.

But when such people join the workforce – as Supermen and women – are they likely to encounter organisational kryptonite at every turn?

A quick look at the spike in Google searches for neurodiversity sees how seriously this is now being taken by all stakeholders. Employers have evolved from seeing such recruitment as corporate social responsibility, to something that has the potential to provide them with game changing skills.

So much has been achieved, yet there is the potential to achieve so much more both for and with the neuro-diverse.